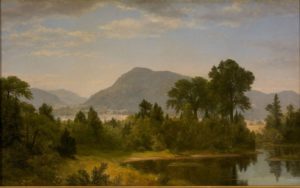

The Museum’s founder, August Heckscher, loved landscape paintings. The founding collection is rich in work from Hudson River School artists who were captivated by the natural world, including Frederic Church, Thomas Moran, George Inness, and Asher B. Durand. Durand was interested in romanticized depictions of the American landscape, extolling “lakes embosomed in ancient forests . . . and many other forms of Nature yet spared from the pollution of civilization.”¹ Durand’s Keene Valley from the late 1860s depicts one such idyllic paradise. Mountains in the background showcase the vastness and grandeur of the American landscape, and the overgrown trees and brush surrounding the lake look untamed and untouched by human hands.

The Museum’s founder, August Heckscher, loved landscape paintings. The founding collection is rich in work from Hudson River School artists who were captivated by the natural world, including Frederic Church, Thomas Moran, George Inness, and Asher B. Durand. Durand was interested in romanticized depictions of the American landscape, extolling “lakes embosomed in ancient forests . . . and many other forms of Nature yet spared from the pollution of civilization.”¹ Durand’s Keene Valley from the late 1860s depicts one such idyllic paradise. Mountains in the background showcase the vastness and grandeur of the American landscape, and the overgrown trees and brush surrounding the lake look untamed and untouched by human hands.

This view of the American landscape as “untouched” was shared by many artists at the time. This idea ignores, however, the Native Americans who lived on and stewarded the land for generations (and who continue to do so today).² Much like Durand, Thomas Moran often depicted the American West as empty of people, and thus available for white ownership, settlement, and tourism.³ In Moran’s Hopi Village, Arizona (1916), we see members of the Hopi Tribe, possibly at Walpi, an adobe village with a thousand-year history, reduced to props in the landscape. To some artists of the time, since the Hopi did not impact the environment in the ways that white people did, they were seen as merely part of the natural world, not as a thriving people living in the area.4

This view of the American landscape as “untouched” was shared by many artists at the time. This idea ignores, however, the Native Americans who lived on and stewarded the land for generations (and who continue to do so today).² Much like Durand, Thomas Moran often depicted the American West as empty of people, and thus available for white ownership, settlement, and tourism.³ In Moran’s Hopi Village, Arizona (1916), we see members of the Hopi Tribe, possibly at Walpi, an adobe village with a thousand-year history, reduced to props in the landscape. To some artists of the time, since the Hopi did not impact the environment in the ways that white people did, they were seen as merely part of the natural world, not as a thriving people living in the area.4

Another interesting facet of Hopi Village, Arizona is the thumbprint Moran added next to his signature on the bottom right corner. He included his print because of the many forgeries of his popular work during his lifetime.5 In fact, in the 1970s, when serious scholarship on the Museum’s founding collection began, art historians discovered that several works the Heckschers purchased were not what they appeared to be. When they acquired Durand’s Keene Valley, they thought they were purchasing an Alexander Wyant painting, given Wyant’s signature on the work. When Wyant’s forged signature was removed by conservators, Durand’s name was revealed. Ironically, while Wyant’s work was considered more valuable than Durand’s in the 1910s, Durand is now considered the more significant artist.6

To help us conserve Durand’s painting, and other works in the collection, visit: http://heckschercollection.org/argus/Portal/MainPortal.aspx?lang=en-US&p_AAFY=c332505d-1532-4530-947f-8f7560f0451d+%5c%7c&p_AAEE=tab7&d=d

To consider Indigenous perspectives on American landscape painting, read:

https://www.metmuseum.org/about-the-met/collection-areas/the-american-wing/native-perspectives.

For a glimpse inside Thomas Moran’s Long Island studio, see: https://artistshomes.org/site/thomas-and-mary-nimmo-moran-studio.

1 A. B. Durand, “Letters on Landscape Painting, Letter II,” The Crayon vol. 1, no. 3 (January 17, 1855): 35.

2 See Karl Kusserow and Alan C. Braddock, eds., Nature’s Nation: American Art and Environment (Princeton: Princeton University Art Museum; New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018), 20, 22.

3 Ibid., 17-19.

4 Ibid., 18, 20.

5 Nancy K. Anderson, ed. Thomas Moran (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art; New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997), 274.

6 Ronald G. Pisano, “Asher B. Durand,” in Catalogue of the Collection: Paintings and Sculpture (Huntington, NY: The Heckscher Museum of Art, 1979), 26.